The 1970’s started with the fanfare of Apollo’s 11 and 12 of 1969. However, Apollo 11, particularly , was a political statement to show the United States technological superiority and to fulfil President Kennedy’s vision of in 1962.

NASA by this time had felt comfortable about sending a manned mission to the Moon. But in 1970 disaster struck with Apollo 13. An explosion in one of the Service Module tanks caused the mission to be abandoned. The astronauts had to use the Lunar Module as a life boat to return to Earth.

After Apollo 13 NASA resumed Project Apollo with missions 14 to 17. These were all science based with landing sites carefully chosen to return the best scientific information about the Moon’s history.

Project Apollo was due to have 20 missions. Unfortunately, public interest in Moon missions had waned and turned to more Earthly problems. Money in the project was cut so the Apollo project was cut short at Apollo 17.

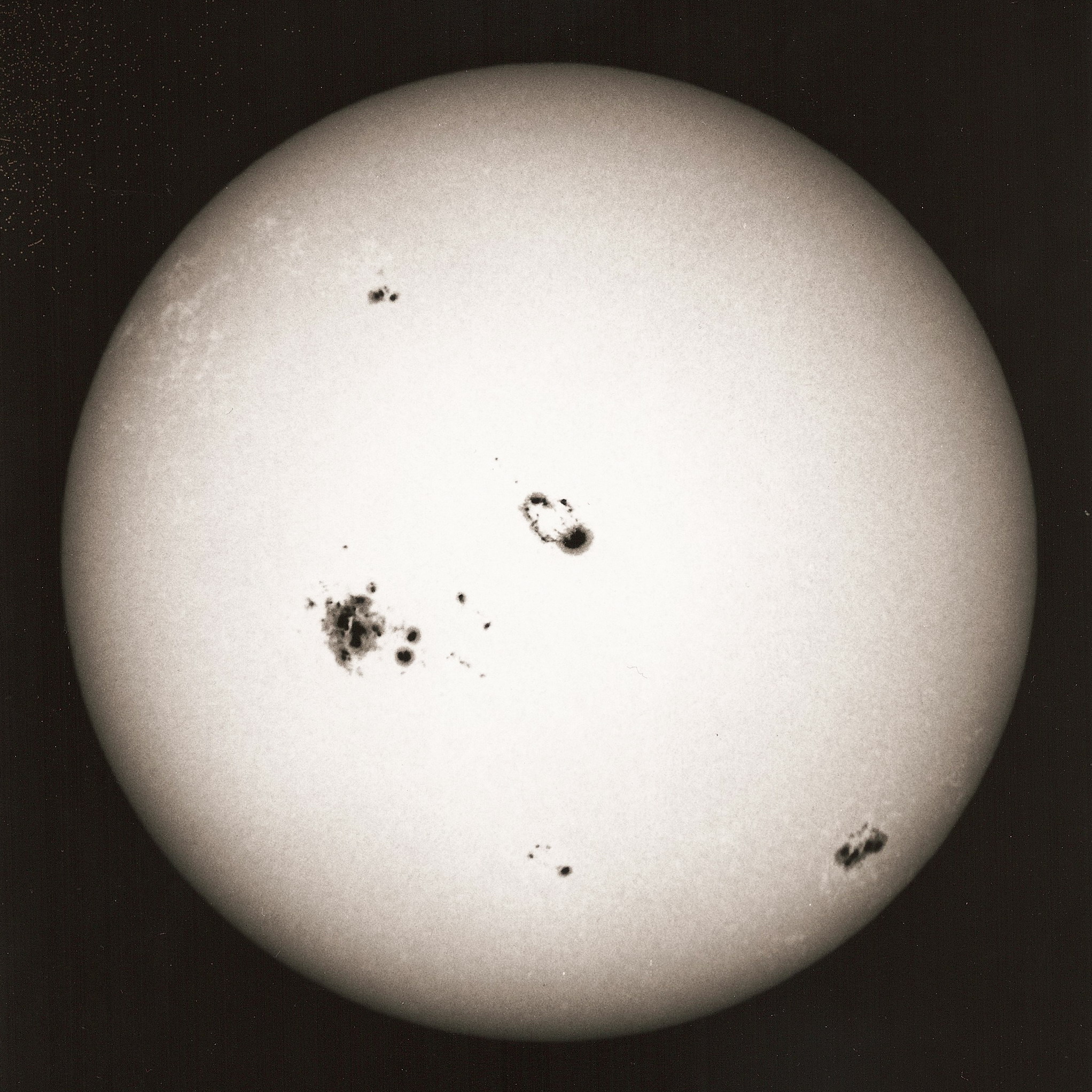

The Soviet Luna programme continued its ambitious journey to the moon with Luna 16, 17, and 24 missions. These remarkable feats were not just about planting flags but also about sending back invaluable samples of the lunar surface. Amidst these, NASA managed to write its own lunar legacy with Apollo 15, 16, and 17. The last of the Apollo missions, Apollo 17, still stands as the final manned mission to the moon to date. Apollo 15 was the first to use the Luna Roving Vehicle or Moon Buggy as it was lovingly nicknamed.

The Missing years in the Exploration of the Moon.

As the 1970’s drew to a close neither NASA or the Soviet Union’s interest in the Moon started to wane. Instead, NASA concentrated on designing the Space Shuttle and launching the Hubble Telescope and send missions to the outer planets. NASA’s last Moon mission was in November 1973 with Mariner 10. Mariner 10 mapped the Moon’s north pole to test its camera’s on way to Venus and Mercury. NASA also sent ISCC, ICE-Explorer, towards the Moon but this was a series of flyby’s on the way to Comet Giocabini /Zinner in August 1978.

In 1976 the Soviet Union sent Luna 24 to the Moon this mission was a success as a sample return but it turned out to be the final probe to the Moon by the Soviet Union. To date Russia has not sent any more probes to the Moon.

During the 1980’s political and economic landscape was changing. This all contrived to cause a lull in the exploration of the Moon. The balance in space exploration was firmly back with the Americans. In 1989 the Soviet Union fell and the Soviet Union ceased to exist.

Both the Americans and the Soviet Union had only each other in the race to the Moon prior to 1990 a third country joined the race. Other countries had sent Earth orbiting satellites but none had sent anything to the Moon

In January 1990 Japan became to third country to impact the Moon with its probe Hiten. Hiten was a duel probe with another probe, Hagoromo. Both probes were designed as flybys but the failure of Hagoromo caused the Japanese controllers to put Hiten into a selenocentric orbit finally impacting the far side of the Moon.

It wasn’t until January 1994 that NASA sent a mission to the Moon. The reason for this was that NASA was looking towards permanent base on the Moon. To do this they needed more detailed maps of the Moon, particularly of the polar regions where it was thought ice could exist. The presence of which could reduce the cost of sustaining a Moon base. Water can be used not only for drinking but broken down into its elements it can be used for supplying oxygen to the air for the colony and hydrogen for fuel. Both would be prohibitively expensive if sent directly to the Moon from Earth.

The changes in the geopolitical and economic background was largely to blame for this gap in Moon missions, especially by NASA. What would have happened if water had been detected on the Moon earlier, would we have seen bases on the Moon in the 1980’s or even 1990’s? The Shuttle was available to send the first astronauts there and as proved by the building of the ISS, International Space Station, the technology was also there.

Return to the Moon

You might wonder why the flurry of lunar missions seemed to suddenly halt in the 1980s. Well, space agencies around the world saw a dramatic shift in priorities. The vigorous race to the moon of the previous decade tapered off as geopolitical and economic landscapes changed. In this period, there were virtually no missions to the moon. This pause often sparks curiosity about what could have caused such a glaring omission in a history rich with lunar exploration.

A confluence of factors contributed to this silence. The global economy of the 1980s experienced significant upheaval. Nations grappled with recessions, oil crises, and inflation. These economic hurdles had a direct impact on government spending, with space exploration budgets facing substantial cuts. The immense cost of sending humans or even robotic missions to the moon couldn’t be justified when more immediate fiscal concerns loomed large.

The political landscape also shifted focus away from lunar endeavors. The conclusion of the Apollo program and the detente phase of the Cold War reduced the strategic imperative for moon missions. Superpowers, particularly the United States and the Soviet Union, turned their gaze to showcase their prowess through the deployment of space stations and the development of the Space Shuttle program, steering clear of the moon’s desolate allure.

During this period, the fruits of space exploration were enjoyed closer to home. Attention pivoted to applications that had more immediate benefits, like communication satellites which revolutionized the way the world shared information. Space shuttles became the workhorses, enabling the construction of regional space stations, space labs for conducting experiments in microgravity, and satellites that monitored Earth’s climate and natural resources.

These developments weren’t without their impact on lunar research, though. The technological innovations of the ’80s—such as advances in computing and materials science—laid important groundwork for future missions. Despite the moon’s temporary retreat from the spotlight, the knowledge and technology base was slowly expanding, setting the stage for a new era of exploration.

As history would have it, by the close of the 20th century, a resurgence of interest in our celestial neighbor was on the horizon. The stage was set, not just for mere return visits, but for smarter, leaner missions that promised a new wealth of discoveries. Our gaze was lifting once again to the ancient and familiar orb, with ambitions fueled by the dawn of a global, cooperative space age.

Renaissance of Lunar Exploration: Smart Missions and New Players

The late 1990s marked a turning point in lunar exploration. Here we saw the rebirth of moon missions, albeit with a different flavor. It wasn’t about the monumental footprints of the Apollo era; this time, innovation and efficiency took center stage. The space community introduced smaller, cost-effective missions that would broaden our understanding of the moon in ways that were not possible before.

One notable entrant that symbolizes this shift is Japan’s Hiten spacecraft, also known as MUSES-A. Launched in 1990, it was not only Japan’s first lunar probe but also the world’s first robotic lunar mission since the Luna 24 in 1976. Hiten’s primary objective was to test and demonstrate new technologies for future missions, and it successfully injected a smaller probe, Hagoromo, into lunar orbit.

Beyond technological progress, these missions were significant for another reason: they represented burgeoning international collaboration in space exploration. Teams across continents shared data and expertise, paving the way for more inclusive, global contributions to lunar science.

Studies of the lunar surface resumed with sharpened focus, benefiting from the low-cost ingenuity of these modern forays. The convergence of pioneering technology and multinational teamwork was clear evidence that a new age of lunar exploration had begun.

The Legacy of Lunar Journeys: From the 20th Century to Modern Enterprises

Reflecting on the progression of lunar missions through the final decades of the 20th century, we are struck by how these extraordinary ventures have become a cornerstone for today’s expanding space ambitions. The perseverance and ingenuity demonstrated in the 1970s and the bold, calculated risks of the 1990s have handed down a rich legacy. Each mission added a layer of knowledge and unveiled new facets of the moon that have been invaluable for the generation of explorers that followed. Technological advancements made in navigating, landing, and collecting data from the lunar surface transformed into tools and techniques now considered standard practice in space exploration.

What’s more, the lessons learned have translated into safer, more efficient space travel. The software designed to operate lunar landers, the robust communication systems to stay in contact over vast distances, and the understanding of how to protect equipment and astronauts in harsh lunar conditions are just a preview of the extensive catalogue of learnings. This inherited wisdom has placed us in a far better position to face the frontiers of space today.

With a surge of interest in the moon from both veteran space powerhouses and emerging players, the stage is set for a new epoch of lunar exploration. Future missions have the benefit of historical hindsight coupled with radical advancements in technology. The aims have evolved: now, there’s talk of establishing permanent bases, exploiting lunar resources and using the moon as a stepping stone for missions further afield.

The recent past serves as a crucial foundation for these ambitions. It’s not just the technological and scientific groundwork that’s been laid — international cooperation, nurtured during those earlier missions, has blossomed, leading to an unprecedented level of collaboration in space endeavors. It’s a testament to the unyielding human spirit to explore and to the enduring value of the moon missions that bridged the 20th century and the new millennium. LOOKING UPWARD, we see not just the legacy of past missions but the gleaming horizon of our future in space.